As Canadian drug deaths rise, programs to keep users safe face backlash

As Canadian drug deaths rise, programs to keep users safe face backlash

By Anna Mehler Paperny

Years into a drug overdose crisis, Canada is facing backlash against government-sanctioned programs such as legal injection sites designed to keep users alive without curtailing drug use.

The British Columbia government has walked back a pilot project to decriminalize small quantities of illicit drugs in public places in the province. Police there also are prosecuting activists seeking to make safe drugs available.

And the man who may become Canada's next prime minister, Conservative Pierre Poilievre, has said he wants to shut down some sites where users can legally consume illicit drugs under supervision, calling them "drug dens."

The backlash reflects growing fears in Canada over the use of narcotics in public spaces, encampments where drug use is seen as common, and the specter of needles in playgrounds. Some critics of the so-called harm reduction programs see a rising number of overdose deaths in Canada as evidence that existing measures are not working.

But public health experts worry that dialing back the programs would endanger the health and lives of drug users, contributing to even more deaths.

"We have a potential to really lose ground on a lot of initiatives that have been started that could really address the opioid overdose crisis in meaningful ways," said Dr. Ahmed Bayoumi of St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto, adding that the backlash was primarily driven by ideology.

A GROWING TOLL

Since 2016, more than 44,000 Canadians have died of opioid overdoses, according to the federal government. Public health experts attribute the toll to a volatile mix of drugs on the illicit market, including fentanyl, which is 50 times more potent than heroin. Users often do not know what's in the drugs they are taking.

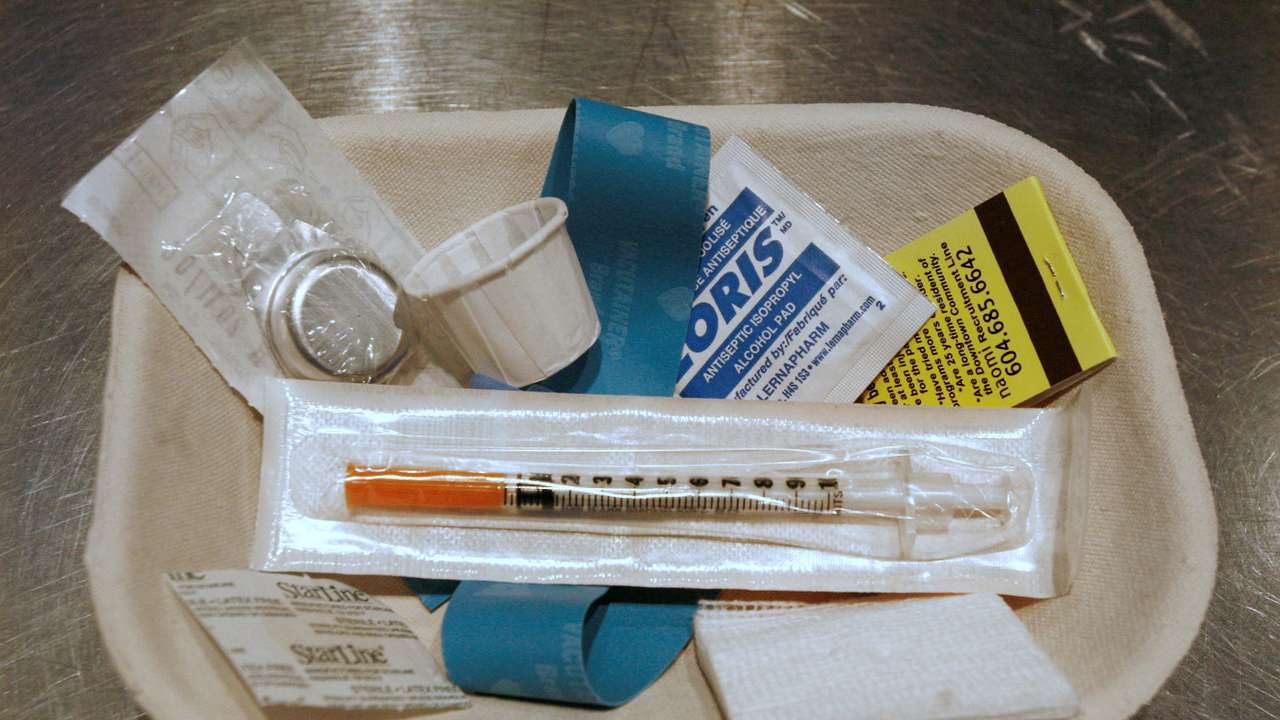

Advocates say harm reduction programs lower the risks of drug use even if they do not prevent the behavior. The approach includes needle exchanges that prevent disease transmission and supervised consumption sites that allow people to take drugs under the care of health workers.

For some, harm reduction includes decriminalizing small quantities of some drugs or prescribing a "safe" supply to users.

In a 2011 ruling, Canada's Supreme Court quashed an attempt to shutter the country's first supervised drug consumption site, in Vancouver. The court found it "saved lives and improved health without increasing the incidence of drug use and crime in the surrounding area."

As of September, there were 39 such sites across the country. Since 2017, they have reversed more than 55,000 overdoses, according to the government. A study published in February found a decrease in overdose deaths in Toronto neighborhoods that had supervised consumption sites.

Earlier this month, Poilievre, who has a wide lead over Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in polls, said if elected, he "will close safe injection sites next to schools, playgrounds, anywhere else that they endanger the public and take lives."

Speaking at a Montreal playground near one such site, he said: "There will not be a single taxpayer dollar from the Poilievre government going to drug dens," adding that "they've made everything worse."

Yuval Daniel, a spokesperson for Canada's minister of mental health and addictions, said evidence demonstrated the social and health benefits of the supervised consumption sites.

Regarding public safety, she said, officials must remain engaged with the communities where sites operate and take measures to address concerns.

Thomas Kerr, director of research with the BC Centre on Substance Use, who has studied the effects of supervised consumption sites, understands the concern.

“I've got kids, too. I don’t want to go to the playground and see a discarded needle,” Kerr said. But studies show supervised consumption sites reduce public disorder, he added, including reductions in discarded syringes.

The questions we should be asking, he said, are: "How do we optimize those programs? How do we make them more effective?"

PROSECUTION AND RECRIMINALIZATION

Vancouver police in May charged two people with possession for the purpose of trafficking for their alleged involvement with a group that openly sold drugs pre-tested for safety to users at cost. The so-called compassion club had sought Health Canada's permission but was denied. Even so, police appeared to look the other way in its first year.

Proponents of the "safer supply" strategy argue it saves lives by giving users an alternative to the illicit market, in which deadly fentanyl and other drugs are increasingly mixed. Detractors says the drugs are often shared or sold to others.

In April, British Columbia walked back the pilot that decriminalized small amounts of drugs such as heroin and methamphetamine, citing public safety, though possession is still permitted in private and in designated facilities. The U.S state of Oregon also recriminalized possession of such drugs earlier this year.

Simon Fraser University criminologist Neil Boyd characterized the backlash as “a growing awareness that the pendulum has swung a little too far."

“I think there is a little bit of an understandable backlash about the extremes,” he said.

But Tara Gomes, principal investigator at the Ontario Drug Policy Research Network, says these initiatives save lives.

"If we take away harm reduction as one of the options available to people, ultimately all I can see happen is we're going to see more people losing their lives. And that terrifies me."

This article was produced by Reuters news agency. It has not been edited by Global South World.